Midwinter Break is all about a past that haunts its main characters, but only in a way that the screenplay (written by Nick Payne and Bernard MacLaverty, adapting a novel by the latter) constantly suggests and rarely confronts. In theory, that’s fine. It could certainly open up director Polly Findlay to the possibility of crafting a character study or, perhaps, a character-based thriller of a low-key sort, in which that haunting past says something about these two people.

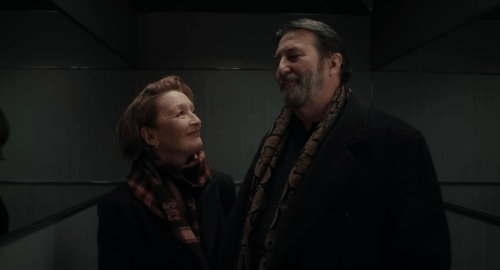

It’s possible, in fact, that the director, making her feature debut, believes that she has done so, launching with a vague flashback to when younger versions of Stella (Lesley Manville) and Gerry (Ciarán Hinds) had their comfortable lives interrupted by violence. All that we learn for a long while is that that violence erupted during the “Troubles,” that awful period of ethnonationalist conflict in which the status of Northern Ireland was being determined (to put it lightly). The story of this movie, though, takes quite a long time to materialize into much of anything.

For a while, we simply watch as Stella surprises Gerry with a trip to Amsterdam, as a way of injecting some activity into their late-middle-aged life defined by stasis and routine: Stella attends an evening church service and returns to find Gerry asleep in the very position that, hours earlier, he was listening to music, and judging by how she handles the situation, it’s neither the first nor going to be the last time that very scenario has happened. Going to Amsterdam, specifically to visit a spot where Irish Catholics settled and formed a secretive place to worship during a country-wide ban, might invigorate their relationship, Stella theorizes.

For those of us in the audience, though, who might want a little more reason to be invested in a story than this, it comes as a disappointment that the movie adds up to little more than a few naturalistic conversations, some pensive music placed over Stella’s ruminative face, and a pair of monologues for each actor that unfortunately reveal nothing more than a bit of exposition. Stella explains (to Kathy, a fellow Irishwoman—played by Niamh Cusack—who expatriated to Amsterdam years ago) some more details about that opening scene. Gerry, an alcoholic in denial, later justifies his emotional reaction to some of the revelations about those fateful events.

That’s about it, though, in terms of real drama, and as a result, one can’t help but wonder whether an adaptation of this novel (which, one supposes, must have had some meat on its bones to get to a certain page requirement) might have worked better as a short film. The film’s generous 90 minutes aren’t so much filled with narrative flotsam as they are abnormally bloated with pregnant silences and a general vibe that we and the characters are just waiting for something—anything—of real substance to happen. Only in the final handful of scenes, as Stella finally takes an active stance in this marriage, does that occur.

Manville and Hinds, both consummate professionals and easy to watch in roles that demand very little from them but credibility, are both good here, though a screenplay that limits their abilities is only going to receive so much from its actors before the strength of that material needs to kick back in. As such, this is not a movie that affords either actor some big moment that stretches or even exemplifies their ability. Even as they credibly deliver those monologues, we’re painfully aware of how empty and how divorced from any emotional context the words are.

This is certainly not the way it should be, given that somewhere buried deep within Midwinter Break is a knotty and tense examination of a long-standing marriage under duress. By focusing entirely on the banalities of their relationship, the filmmakers only succeed in wringing out all signs of drama, nuance and tension from its alleged study of characters in late-life crisis.

Rating: *½ (out of ****)

Leave a comment